Introduction

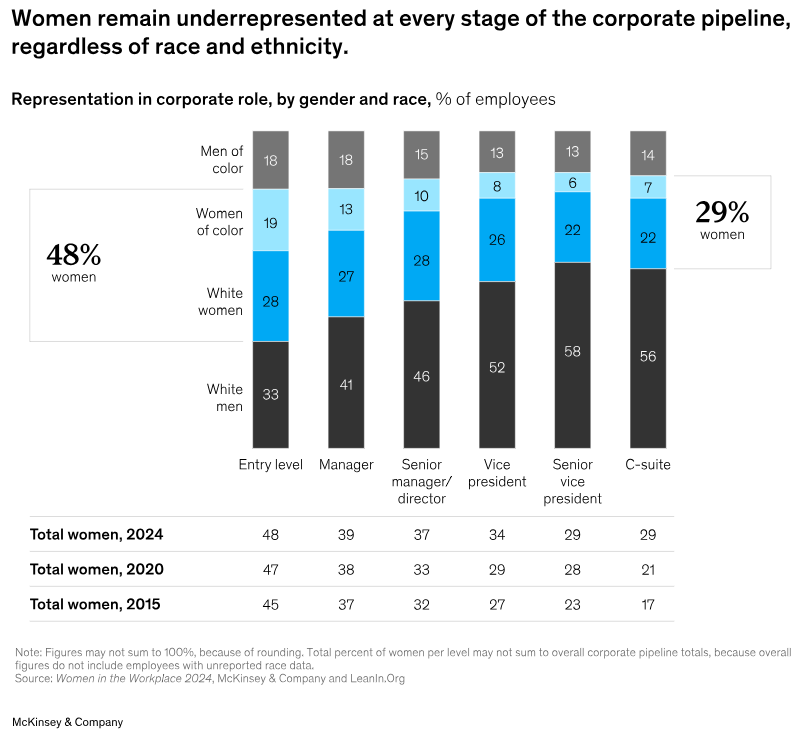

A recent report in McKinsey titled Women in the Workplace 2024: The 10 Year Anniversary Report offered some fairly underwhelming numbers on gender equity, parity, and representation. The numbers are based on “the largest study of women in corporate America,” which they conducted over the past decade. Over 1,000 companies participated in the study, and the researchers surveyed more than 480,000 people about their workplace experiences. The long and short of the report is summarised well with the figure below:

It’s not what I would consider the most inspiring of percentages. It is nearly as disappointing a read as the Global Gender Gap Report 2022 by the World Economic Forum. It found that worldwide, only 33% of senior leadership positions are held by women and, at current pace, it will take 151 years to close the global gender gap regarding economic participation and opportunity. Gender bias has been identified as one of the contributing factors to these appalling numbers (Algner et al., 2024; Hentschel et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2016; Kossek et al., 2017).

As reports of general lackluster leadership representation for women are being published, so are studies and papers on the impact and value of women leaders. A recent paper by Gierke, Schlamp & Gerpott (2024) titled, Which organisational context factors help women to obtain and retain leadership positions in the 21st century? A systematic review and research agenda for human resource management highlights the benefit of attracting and retaining women in leadership roles. The authors write how “gender diversity (among other diversity markers) within the workforce (Dai et al., 2019; Østergaard et al., 2011), and on organisational boards (Khushk et al., 2023; Makkonen, 2022) is positively associated with enhanced innovation performance. Moreover, a higher representation of women on boards is positively linked to improved firm performance,” (Gierke et al., 2024, pg. 3).

This begs a question: If diversity is positively associated with enhanced innovation and women on boards is positively linked to improved organisational performance - what’s the hold up???

Disappointing and unsurprising outcomes reported in studies on gender bias experienced by women leaders suggest this particular bias hangs around like a bad smell. (My words, obviously.) Algner, Fay, and Lorenz (2024) write about gender bias appearing to contribute significantly to the gender disparity observed in upper leadership positions in their study on the Gender Bias Scale for Women Leaders by Diehl, Stephenson, Dzubinski & Wang (2020). It seems that the research demonstrating positive links between women leaders and desirable organisational outcomes is no match for bias. Like, I said, disappointing.

Side note…

When posting her work on LinkedIn, the lead author of the study on the GBSWL, Mona Algner, posed a question. She asked: Why do you think women’s motivation to lead sometimes increases after experiencing gender bias?

Is it because we know it’s unacceptable? Because we know we’re skilled, knowledgeable and competent - and hearing the opposite whilst seeing mediocre performance receive praise is both unpalatable and exigent.

What is there to be done?

So much. But let’s keep this in the neighbourhood of concise. In the McKinsey report referenced in the introduction, there are several recommendations provided to improve gender imbalance at work.

Let’s focus on two:

De-bias hiring practices and performance reviews

Maintaining and/or scaling up programmes designed to advance women

What might this look like in practice:

DE-BIAS HIRING

Develop clear evaluation criteria before considering candidates; bias train those who are evaluating; aim for diverse lists of similarly qualified candidates; anonymise the process

Use gender-inclusive language rather than masculine-as-neutral in your hiring ads and role profiles; rewrite job ads to include encouragement for women to apply

Attract more women by offering more work flexibility; for much more on women and flexible work, see Prof Heejung Chung’s work like this excellent white paper on talent and flexible work.

If you are less interested in a gradual approach (and have the power to do so), take a leaf out of Eindhoven University of Technology’s book. In response to no change in hiring outcomes, it was decided to only hire women for a year.

2. PROGRAMMES DESIGNED TO ADVANCE WOMEN

If you’re reading this with little space in your current role to tackle the cultural or structural levels, an individual action you can take is to work on developing your agentic traits. It turns out agentic traits are still considered prototypical leader attributes, although communal attributes have become less detrimental over time (Bandura et al., 2018) Agentic traits include: Assertiveness, Ambition, Competence, Self-Efficacy, Independence, Self-sufficiency, etc.

It may also be useful to develop other leadership skills like those highlighted in Ibarra’s HBR article on what she refers to as The Authenticity Paradox. Very briefly, her argument is that it’s okay to be inconsistent from one day to the next. In fact, we need to experiment to figure out what’s right for the new challenges and changing circumstances. Her recommendations for being authentic in a way that is skillful at work include:

Learn from diverse role models

Work on getting better - devote real time and energy to this, not just talk. Set goals for learning

Don’t cling to your ‘story’ - stories become outdated and we need to evolve. Think of your growth and the evolution of your ‘story’.

Those are two individual programme-esque approaches you can take to advance yourself.

***

Let’s consider more organisation-wide actions.

Consider the narrative your organisation has - that is, consider how the use of language, assumptions, and storytelling are unnecessarily gendered. An excellent way to step out of a social defense that sustains intergroup inequality is to reject a gender attribution to roles and work activity. For example, rejecting language that devalues a leader’s contribution because they’re a woman. Leave in the past the masculinized ideal worker norm (Padavic, Ely & Reid, 2020) where everyone on your team(s) is available all the time. Incidentally, that’s an excellent way to encourage burnout.

Consider structural-level changes that can improve gender parity as an output. For example, choose an opt‐out instead of an opt‐in mechanism for leadership succession, such that all potentially eligible employees are automatically considered for an open leadership position unless they opt out of the promotion process. Evidence suggests opt-in succession design creates a gender gap (Erkal, Gangadharan & Xiao, 2022).

Communicate clearly by being transparent and systematic in demonstrating how leaders are chosen. This is again about language (e.g., gender-neutral terminology), but also about representation and sponsorship (i.e., championing women, being a ‘bridge’, being aware of gender bias, etc.) Build these components into a better people-focussed strategy for development and succession.

Recap

Women in leadership positions are positively linked to desirable organisational outcomes. Unfortunately, women remain under-paid, under-promoted, poorly represented, and overlooked for leadership positions. Fortunately, organisations can use evidence-based practices and policies to obtain, retain, and uplift women in leadership roles. Consider how you might put some of these innovative practices to work in your context.

Good luck, Professionals!